Introduction

Does your organization spend too much time and effort gathering market and competitive intelligence (MCI), only to struggle to find the right insights when needed? The issue isn’t a lack of information, but disorganization with unstructured data, scattered across multiple sources, making it difficult to retrieve and analyze.

Organizations need a systematic way to organize and label information, making it easier to index, search, and extract meaningful insights. That is exactly what Taxonomy helps you accomplish. It a structured way to categorize and name information for better indexing, searching, and insights.

Despite its importance, taxonomy is often overlooked, leading to inefficiencies. In this blog, we break down why taxonomy matters, how to build one effectively, and the best practices for maintaining it; drawing from real-world experience at Contify. Let’s dive in.

The Impact of Poor Information Organization in Organizations

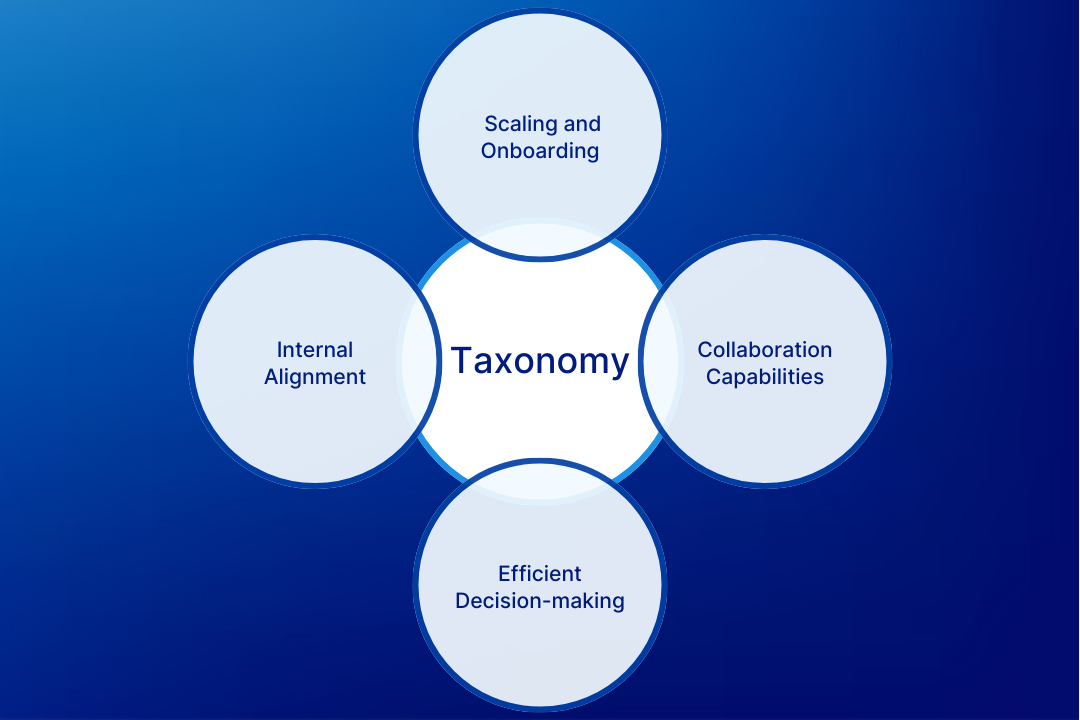

Time is of the essence for present-day companies as they operate in a fast-changing and complex environment. However, the lack of taxonomies leads to several challenges:

1. Inefficient Decision-Making

Decisions are only as good as the information available. When employees cannot easily find relevant intelligence, they either waste time searching or make choices based on incomplete data. This leads to reactive decision-making instead of strategic action.

2. Misinformation and Internal Misalignment

When teams work with fragmented information, they develop different understandings of market conditions, competitors, and even internal capabilities. This results in conflicting viewpoints, unnecessary debates, and inefficiencies in execution.

3. Breakdowns in Collaboration

Valuable insights often exist within the organization but are not shared effectively. Sales teams may discover competitor movements before marketing, while customer service may identify recurring product issues before the product team. When this information is not accessible across teams, organizations fail to act promptly.

4. Difficulties in Scaling and Onboarding

As organizations grow, new employees need access to existing knowledge. Without a structured information system, onboarding becomes time-consuming, and knowledge transfer is inconsistent. This slows down individual productivity and overall organizational growth.

Poor information organization weakens efficiency, reduces agility, and limits competitiveness. By implementing a structured taxonomy, organizations can streamline knowledge management, improve collaboration, and ensure that intelligence is readily available when needed.

Despite these clear benefits, many organizations still struggle to adopt taxonomy effectively. Next, we’ll explore the challenges that prevent its implementation and how to overcome them.

Why Organizations Continue to Struggle with Structuring Information

Most organizations struggle with organizing information effectively because traditional methods rely on single-dimensional categorization. Our natural tendency is to think of information like physical objects, stored in one place, under one category. This approach, while simple, becomes ineffective when dealing with large volumes of dynamic information.

1. Information is Multi-Dimensional

Unlike physical files, digital information can belong to multiple categories at once. A job description, for example, can be classified by function (HR, Marketing), business unit (Product A, Service B), location, or seniority level (Junior, Mid-Level, Senior). Manually tagging information across all relevant categories is time-consuming and inconsistent, especially when users have different interpretations of how to classify it.

Without a predefined taxonomy, tagging becomes chaotic, reducing the effectiveness of information retrieval and analysis.

2. Multiple Teams Have Different Use Cases

Different teams rely on the same information for different purposes. For instance, Contify provides market intelligence feeds to some companies that our marketing team classifies as competitors, while our sales team sees them as customers.

Without a well-defined taxonomy, these conflicting perspectives can create inconsistencies in how information is organized and used.

3. Information, Users, and Use Cases Constantly Evolve

Market dynamics, business needs, and available data sources change over time. A rigid taxonomy that does not adapt can quickly become outdated, leading to inefficiencies.

For example, one Contify user built a taxonomy to track competitor acquisitions by categorizing them based on geography, employee count, revenue, and product offerings. Over time, they expanded this approach to analyze partnerships, leadership changes, and office expansions, allowing them to anticipate competitors’ strategic moves.

However, when a key competitor was acquired by a larger company, their existing taxonomy was no longer sufficient, it had to evolve to track new competitive threats. Had their taxonomy been rigid, it would have failed to provide relevant insights, reducing its overall value.

4. The Need for a Flexible and Scalable Taxonomy

There are a few things to consider when building taxonomy successfully, such as:

- Accommodate multiple perspectives across teams

- Ensure consistent tagging and classification

- Adapt to new information and evolving business needs

With this understanding, let’s explore how to build and maintain a taxonomy that ensures long-term scalability and effectiveness.

Get Started with Building Effective Taxonomy

Creating taxonomy begins with gathering relevant terms that align with the intended use-case and users. A common mistake is structuring taxonomy based on available information rather than user needs.

To ensure a well-structured taxonomy, it’s important to start by gathering the right terms systematically. Learn more about how to gather terms for your taxonomy.

1. Identify Relevant Terms

The terms included in the taxonomy should:

- Be clear and intuitive for users.

- Have minimal overlap to maintain consistency.

- Align with the core use case, not just existing content.

For example, if your competitive intelligence includes job postings, include related terms only if they are relevant to strategy teams, not just because the data exists.

2. Manual Content Review

Review sample content like news, reports, presentations to identify commonly used terms and inconsistencies. Different users might refer to the same concept differently, such as “layoffs” vs. “cost-cutting”.

3. Leverage Existing Taxonomies

Many organizations already have informal taxonomies embedded in:

- Website navigation and competitor sites.

- Analyst reports and industry standards.

- Existing folder structures within teams.

Try manually tagging sample content with potential terms to refine the selection.

4. Conduct User Interviews

User interviews help uncover how and why teams use information. Instead of asking how they currently organize data (which may be flawed), focus on:

- Why do they need specific information?

- Where they expect to find it.

- What terms do they naturally use when searching?

| Before asking your users what information they need, how they get that information, and how they will use it, ask why they need the information. |

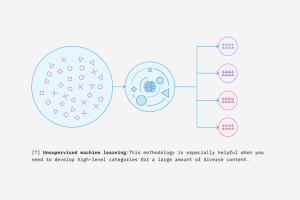

5. Use Automated Methods

For large datasets, automated techniques can identify key terms:

- Unsupervised Machine Learning clusters similar content, revealing hidden patterns.

- Keyword Clouds highlight frequently occurring terms.

- User Search Queries provide insights into the most commonly used terms

Structuring a Scalable Taxonomy

Once relevant terms are identified, the next step is organizing them into a structured, scalable taxonomy. A well-designed taxonomy balances clarity, consistency, and adaptability to evolving business needs.

1. Define Clear Naming Conventions

Ensure terms are simple, intuitive, and unambiguous. Avoid jargon, abbreviations, and overly broad categories. Use industry-standard terminology where possible.

2. Maintain a Logical Hierarchy

Structure categories in a way that reflects how users think. Group related terms under broad categories and refine them into subcategories to improve searchability.

3. Balance Flexibility with Consistency

A rigid taxonomy can become obsolete, while an overly flexible one can create inconsistencies. Design a structure that can accommodate new terms and changing use cases without disrupting existing classifications.

4. Use Synonyms and Metadata

Include alternative terms and synonyms to improve searchability. Define relationships between terms (e.g., parent-child, related terms) to enhance usability.

5. Standardize Governance and Updates

Taxonomies require ongoing refinement. Establish governance policies to manage updates, ensure consistency, and adapt to evolving intelligence needs.

By following these principles, organizations can build a taxonomy that enhances knowledge retrieval, decision-making, and collaboration across teams.

Guidelines for Building Taxonomy

Follow these quick steps to build effective taxonomies:

1. Choose a Taxonomy Structure

Group the selected terms into a formal structure based on the use case. The taxonomy can be a simple list or a complex system with interlinked relationships.

2. Define the Method for Building Taxonomy

- Deductive (Bottom-Up): Users or subject experts categorize terms, starting with broad categories and refining them into consistent hierarchies.

- Inductive (Top-Down): Used when historical content is unavailable. Terms are added gradually as they appear in new content, forming broader categories over time.

- Hybrid Approach: A mix of both methods is often the most effective.

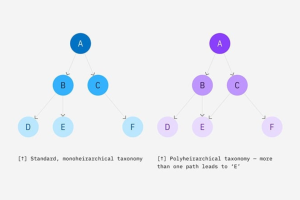

3. Understand the Types of Taxonomies

- Standard Hierarchy: This is a single-root structure with parent-child relationships (e.g., Automobile → Autonomous Cars).

- Faceted Taxonomy: This refers to multi-dimensional classification that allows content to be categorized under multiple independent facets (e.g., Competitors + Topics = Competitor Partnerships).

- Polyhierarchy: When a term appears in multiple categories (e.g., Legal under both Regulatory and Business Challenges). While helpful for tagging, it can create ambiguity.

4. Optimizing Taxonomy for Market Intelligence

- Limit top-level facets by keeping them between 10–15 to maintain simplicity.

- Avoid excessive levels of taxonomy. Anywhere between 2 to 4 levels deep ensures quick navigation.

- Prioritize ease of use over tagging efficiency by opting for a user-centric design.

A well-structured taxonomy evolves with businesses, meaning there are a few things you should look for when implementing software for taxonomy management.

Software Considerations for Taxonomy Implementation

With the explosion of information and new media types, effective taxonomy management requires sophisticated software. Key considerations include:

- Browsing, searching, and exploring: Users should be able to easily navigate the taxonomy, view parent-child relationships, synonyms, and definitions, and search beyond term names to include scope definitions and related terms.

- Automated tagging: Accurate tagging is crucial but challenging. A hybrid approach combining machine learning with human oversight, like Contify’s system, ensures consistency and efficiency.

- Suggesting new terms: The software should analyze search patterns and use machine learning to suggest new terms or synonyms based on clustering techniques.

- Workflow management: Taxonomies evolve. The software should support adding, deleting, merging, and modifying terms efficiently.

- Re-indexing: Updates should apply retroactively, ensuring archived content aligns with the latest taxonomy without manual intervention.

- Reporting: Essential reports include tagging accuracy, manual corrections, missed tags, and historical changes, aiding in taxonomy audits and maintenance.

- Downloadable taxonomy: Users should be able to export a structured taxonomy, including term relationships, scope definitions, and modification history.

- User support: Integrated error reporting, change requests, and in-app support enhance usability. Contify’s in-app chat is a valuable feature.

- Additional features: Excel remains a useful tool for initial taxonomy development due to its simplicity and familiarity. Compliance with Unicode ensures compatibility with diverse languages.

Effective software ensures a dynamic, scalable taxonomy that evolves with business needs. Choosing the right platform as per your organization’s M&CI needs has a plethora of benefits. Let’s check them out.

The Benefits of Choosing a Platform with Advanced Taxonomy Tagging

A well-structured taxonomy reveals the underlying information framework within an organization, ensuring users can access insights in the right context.

Since taxonomy is not a one-size-fits-all model, selecting a platform with advanced tagging capabilities is crucial for effective implementation. Listed below are some common taxonomy benefits that organizations experience with the help of a robust taxonomy management system.

- A Dedicated Core Team: Successful taxonomy implementation requires a cross-functional team responsible for development and maintenance. A leadership sponsor is essential to drive adoption and manage change effectively.

- Measurable ROI: Start with a focused use case that demonstrates clear benefits. Metrics like reduced time spent searching for information can help justify investment, even if measuring ROI isn’t an exact science.

- Seamless Integration of Folders and Tags: Users are accustomed to folder-based organization, but taxonomy-based tagging introduces a multi-dimensional approach. A hybrid model, such as Contify’s centralized intelligence hub. Our platform’s single source of truth bridges this gap, ensuring information remains accessible in a structured yet flexible manner.

A platform with robust taxonomy tagging ensures organizations can efficiently manage information, enhancing competitive intelligence and decision-making.

It’s Your Chance to Turn Chaotic Data Into Structure

Organizations that embrace a well-structured, scalable taxonomy gain a competitive edge. By systematically organizing and tagging intelligence, businesses can enhance decision-making, collaboration, and efficiency.

Choosing the right M&CI platform that balances automation with human oversight ensures long-term adaptability. With Contify, you can turn scattered data into actionable intelligence, unlocking the full potential of market and competitive insights.

Ready to make the most of your

Organizations that embrace a well-structured, scalable taxonomy gain a competitive edge. By systematically organizing and tagging intelligence, businesses can enhance decision-making, collaboration, and efficiency.

Choosing the right M&CI platform that balances automation with human oversight ensures long-term adaptability. With Contify, you can turn scattered data into actionable intelligence, unlocking the full potential of market and competitive insights.

Ready to make the most of your M&CI efforts? Take the Contify free trial today.